The gorgeous colonial architecture invites inspection, and the baroque cathedral downtown is perhaps the single finest example of the ornate Churrigueresque style to be found in Mexico…

Zacatecas had never been particularly high on our list of cities to visit in Mexico, but not long ago it was on our way to somewhere else, so we decided to spend a night or two there. When it was time to leave, we wished we didn’t have to go.

The climate was delightful, clear, sunny, verging on arid, and refreshingly cool, which made for comfortable walking conditions in a postcard picturesque city nestled between two hills. One isn’t constantly dabbing sweat off one’s brow and wondering whether the morning’s application of deodorant is still doing its thing, though the nearly 8,000-foot altitude and narrow, twisty, cobblestone streets which rarely traverse flat ground can be aerobically challenging.

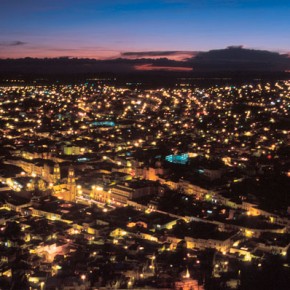

Zacatecas’s glory days as the hub of the country’s mining industry in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have long since passed. Nevertheless, this colonial city of about 150,000 people boasts a sprawling university, a still-functioning mine, an amazing cathedral, an impressive array of museums, and a European-built teleferico (cable car) that flies over the downtown area from 500 feet up, treating its riders to a thrilling five minutes hanging above the city for a third of a mile.

Founded in 1546, Zacatecas is a Nahuatl word meaning a place where grass (zacate) is plentiful. We got there by taking the overnight La Linea Plus bus to Guadalajara from Zihuatanejo (around eight hours, 540 pesos), then hopping on an Omnibus de Mexico coach for the five and a half hour ride (about 325 pesos) to Zacatecas. The final curvy descent into town is quite impressive. By a bit after 1 p.m., we were looking for the #8 combi (micro-bus) to cover the final three kilometers into el centro (downtown), where numerous well-equipped hotels are located. Visit in spring during the off season, and you’re likely to find deeply discounted accommodations in this Unesco World Heritage site.

If you’re feeling flush, stay at the Quinta Real Zacatecas, constructed around the ruins of the oldest bull ring in North America and next door to the photo op sixteenth century aqueduct, Aqueducto El Cubo. Some consider this to be Mexico’s most beautiful hotel. Have a drink at the bar situated near where toreadors (bullfighters) once waited their turn to dazzle crowds and you decide.

Wandering around town, nets you opportunities to visit about ten different museums, including two named after native sons of Zacatecas–the Coronel brothers. Both twentieth century artists who donated their extensive collections, Pedro Coronel’s museum features a worldwide collection of ancient and modern art, while Rafael Coronel’s is dedicated to Mexican masks. The displays change often given that there are around 4,500 pieces in the collections.

The gorgeous colonial architecture invites inspection, and many guidebooks tell you the baroque cathedral downtown with its oodles of statues, built from locally quarried pink stone, is perhaps the single finest example of the ornate Churrigueresque style to be found in Mexico. Interestingly, the color of that stone seems to change as the sun goes down. Check out some of the old mansions and palaces as well, many of which are painstakingly and elaborately decorated. One of the websites I checked before we embarked on our trip said buildings often took years to complete because the architects wanted to leave something special and memorable behind.

Be sure to take a walk around the many downtown plazas at night, when they’re clogged with locals strolling about, way past dark. You’re likely to get stared at quite openly since foreign tourists are not that common. Little garbage and few beggars add to the appeal. This is one of several Mexican towns boasting strolling callejoneadas, raucous little ragtag music bands often accompanied by a burro carrying a cargo of mezcal for the thirsty entertainers. Find something to pound, clank, blow or strum and join the group if you like. Local lore says miners used to end their work week on Saturday afternoons this way.

Now about the mining: There’s still an active 200-year-old mine called El Bote in town, but the biggest tourist attraction is Mina El Eden, which for 400 years was the area’s major source of wealth. The city of Taxco, in Guerrero, is more popularly known today for “working” silver and its many silver designers, but this Zacatecas mine once was the largest silver-producing mine in Mexico, in addition to yielding quartz, copper, gold, calcium, zinc, and iron.

To get there, hike up to the Cerro del Grillo (Cricket Hill) cable car station or take a taxi. The mine entrance is nearby. Pay your 70 pesos, don your gauzy “shower cap” and helmet, and follow your guide along lighted walkways on the fourth of the mine’s seven levels. The lower ones are flooded, and the tour makes no attempt to sugarcoat the awful conditions faced by employees, as young as twelve, in past centuries. (Excavating operations ceased in the mid-1950s.) Adults often worked sixteen hours a day, and too many of the workers (we were told as many as five a day) left by way of slings, fashioned to transport the dead back out. But it’s eerily beautiful too, enhanced by underground pools, a waterfall, and narrow passageways literally chopped from the earth’s innards, walled by stone on both sides.

In the “olden days,” Spanish treasure ships and Manila galleons sailed away with the lion’s share of this silver, much of it made into coins fancifully named, “pieces of eight.” Today there are two shops selling silver pieces as well as mineral samples inside the mine; I bought several incense holders at bargain prices. A narrow gauge railway brought us back up from 1,700 feet deep inside Cerro del Grillo, where I emerged above ground with a new appreciation for unfettered space and fresh air.

For a once-in-a-lifetime experience, come back to Mina El Eden late on a Thursday, Friday, or Saturday night to enjoy the revelry at Disco El Malacate. Although the disco opens its doors at 9:30 p.m., we’re told the joint really starts rocking after midnight and doesn’t wind down until dawn. Ladies get in free on Thursdays; otherwise plan on forking over a 150 peso cover charge.

We also took the cable car ride to the top of the city’s second (and higher) hill, Cerro de la Bufa. The car holds fifteen people or 2,640 pounds. I admit to being a tad leery when one of our fairly large group turned out to be a fellow who must have weighed in at around 400 pounds all by himself, but we made it intact despite his jokes midway across that perhaps this particular ride should have been limited to just half a dozen live bodies.

La Bufa (as the locals call it) is lighted up at night, and our room at Hotel Condesa (430 pesos for a double) offered a great view. It looked so high from our window that we were surprised when it took only twenty minutes to walk all the way back down to street level after we saw the chapel, the museum, and the three larger-than-life equestrian statues up top. There are varying explanations for La Bufa’s name, but my favorite claims the Spanish, arriving in the mid-sixteenth century, thought the unusually shaped rock at the crest of the hill looked like a pig’s bladder, which back then was an object often used for holding wine, in which case it was dubbed una bufa, hence the name that stuck. The little chapel is dedicated to the patron saint of miners. Both the museum and the three statues commemorate Pancho Villa’s 1914 victory over Mexican President Huerta after fierce fighting on the hillside, giving the revolutionaries control of the city and a shot at taking over the nation’s capital city. There’s also a meteorological observatory and a mausoleum of heroes from the mid-nineteenth century to the present decorating La Bufa.

All in all, we’d recommend a visit to this high plateau several states north of Zihuatanejo, which has almost nothing in common with our sea level paradise.

- Zacateces at night. Photo by Carlos Sanchez.

- Teleferico (cable car) over Zacatecas. Photo by Jacom Stephens.

- Zacatecas Cathedral. Photo by Carlos Sanchez.

- Quinta Real, Zacatecas, with the Aqueducto El Cubo in the background. Photo by Carlos Sanchez.